HOPI PROPHECY AND GUN TECHNOLOGY

This is the second in a series of three blogs about the Hopi prophecies. In the first blog published on line last month, the relationship of the prophecies to current electro magnetic technology was explored. It’s important to understand that the Hopi prophecies do not focus on the idea that all technology is bad. Rather, part of their message is that humans need to have the awareness that technology is powerful. It must be approached with discernment. The prophecies offer the wisdom that it is important to work skillfully with technology that does no harm, that benefits nature and all living beings (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EeJ2e70OXDw).

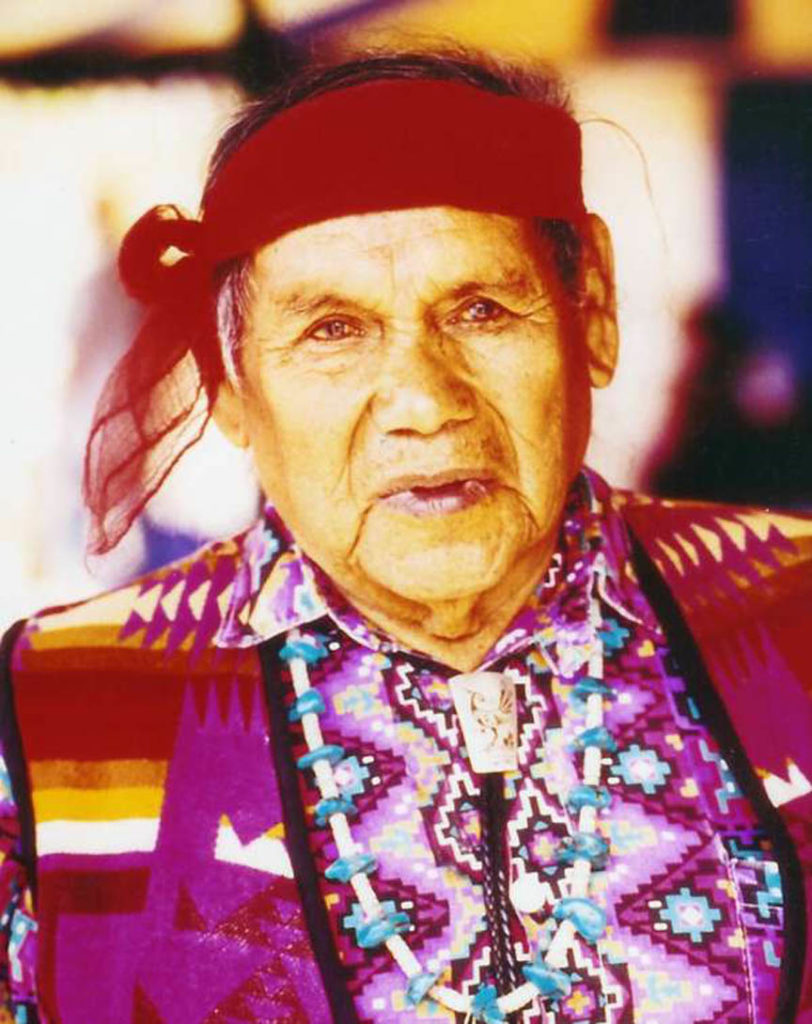

I was already familiar with the Hopi prophecies through Grandfather David Monongye when I heard that Grandfather Thomas Banyacya, a peer of Grandfather David and another holder of the Hopi prophecies, was going to speak at the Unitarian Church in Santa Fe. This must have been in 1991 or ’92. Sitting in the packed audience, hearing Grandfather Thomas speak simply and directly about his life in relationship to the prophecies, struck me deeply. Like Grandfather David he was a remarkably dedicated person, with the drive and courage to hold to his traditional path no matter what the consequence. He and his wife Fermina had fought the incursion of Peabody Coal and its impact on native lands and peoples for decades. Another period of his life that especially got my attention was how he as a young man worked with World War II. He had already been a part of a small group of Hopi youth initiated into the Hopi prophecy teachings when World War II began. Both world wars were depicted on Prophecy Rock. Hopi people do not oppose the bearing of arms per se. However, at the onset of WWII, Thomas looked carefully at the issues and motivations, and consciously decided he would not serve in the US military. This was not his war; it was not his battle. For this strong and conscious choice, he served seven years in federal prison as a conscientious objector in the 1940s. He spoke about this time to all of us on that day. Inspired by all that he had said, I went up to him after the talk and asked if he had ever thought about writing his autobiography, or writing it with someone. He looked at me and said, if I was interested in talking with him further about this, I could come to meet with him in his home in northern Arizona.

Our daughter was a toddler at the time and I had not left her for any extended period at all. Yet it felt quite important, and our family talked it over, and when I could, I drove myself out to Kykotsmovi, Arizona to talk more with Grandfather Thomas about this. He and Fermina put me up in their home. I was kind of amazed at how happy I was for those few days, once I got over my initial internal culture collisions. (At one point early on in the visit I had been hard at work at Grandfather Thomas’s request on a letter to the United Nations. I had been pecking away on an ancient typewriter in one of the small back bedrooms, quite absorbed. I came out to ask him something in the not very big kitchen, where everybody met, where all the discussions happened. As I stumbled over the threshold, I found myself in a room filled with Indian people. Old Iroquois friends had stopped by to see Thomas and Fermina on their way across the country. I was shocked to find that I was scared to be the only white person in the room! Everyone was kind; no one was directing hostility toward me. It was my own issue. I had no idea that this was part of what I had absorbed from all those old cowboy and Indian westerns I’d seen as a kid. It was embarrassing to see how unnecessarily fearful I was.

During that time in Hopi, I got a deeper sense of the respect the Hopi people hold for the earth and their traditions. It was inspiring and humbling. They were very practical. They were quite willing to work with technology, yet not at expense to themselves or their culture. If a technological practice caused harm, they were not in support of it. They actively joined with other indigenous people, like the Iroquois elders, to oppose what they saw as changes that harmed the planet and its beings. They saw themselves as caretakers for the earth; they took this responsibility seriously.

I have thought about these teachings in relationship to our country’s intense debate over gun control right now. In the last blog I asked, how can we wisely and safely transition to this more respectful and sane Hopi Path of Life? How can we make this a reality? Our president has just made a clear stand to control some of the most dangerous gun technologies, those that exist only for war. This can be one crucial way to affirm the ancient path of wisdom the Hopis describe. It limits harm to humans, other sentient beings, and the earth.

Malcolm Byrne of Gorey (yes really), Ireland, put it well in a letter to the editor of The New York Times on October 3, 2015. He wrote, “After a shoe bomb attempt in 2001, shoes often have to be removed at airports. A failed liquid bomb attempt meant restrictions on liquids being taken onto planes. Could the United States please explain why after almost daily mass shootings in your country, no action is taken? Are shoes and shampoos really more dangerous than guns?”

Other countries have responded to mass shootings with coherent changes in laws and regulations, without eliminating the right to bear arms. To date, we have been unable to do this, unlike Australia, Canada, and Britain. When a man armed with a semiautomatic killed 35 and wounded 23 more people in Tasmania in 1996, the national outcry in Australia was so strong that “tight restrictions on firearms, including a ban on almost all automatic and semiautomatic rifles, as well as shotguns” ensued. (New York Times, Oct. 3, 2015, A16) The new prime minister at that time, John Howard, said that it was not an easy process. The legislation included a giant state by state gun – buyback program that destroyed more than 600,000 weapons. In 2013, Howard reflected back on this time, saying, “In the end, we won the battle to change gun laws because there was majority support across Australia for banning certain weapons.” He added, “Few Australians would deny that their country is safer today as a consequence of gun control.”

A life-affirming path like the one the president is proposing can only succeed with massive support. As citizens of the US, if we wish to create such change, we must actively stand for it.

I am reminded of a Tibetan Buddhist teaching, probably on the six bardos, that I heard some years ago. The Venerable Traga Rinpoche, founder of Rigdzin Dharma Foundation in Albuquerque, New Mexico, was asked (through a translator) what does one need to do if one finds oneself in Hell? His reply was simple: “Think of the others.”